The Hidden Value of Privately Owned Public Spaces

Ever see a random open space with odd hours and basic seating — probably a POPS

Earlier this past winter, while trying to find a spot to meet up with friends to go on a run along the Two Bridges, we unexpectedly discovered a public space in the financial district — 60 Wall Street. With its large open floor plan, various chairs and tables, and direct connection to the subway, the indoor plaza looked like a perfect spot as a great free starting point to stretch and keep warm, before heading out for our run in the cold windy evening.

We kept coming back to meet here for the rest of the winter, each time with different parts of the space gradually getting closed off, boarded up with signs stating that there were plans for new renovations.

It was only later that I learned what 60 Wall Street is and how many places like 60 Wall Street exist across New York City.

Finding POPS Around the City

A space like 60 Wall Street is what’s known as a privately owned public space, or POPS.

Like traditional public spaces, these places are dedicated for public use and enjoyment, often with spots to sit and relax, decorated with plants and open areas. Most often, they can look like public plazas or cafe-areas in parks. When done well, these POPS can provide the same value as typical public spaces, fostering strong social interaction places for community and culture building, promoting better overall health, and creating a sense of place.

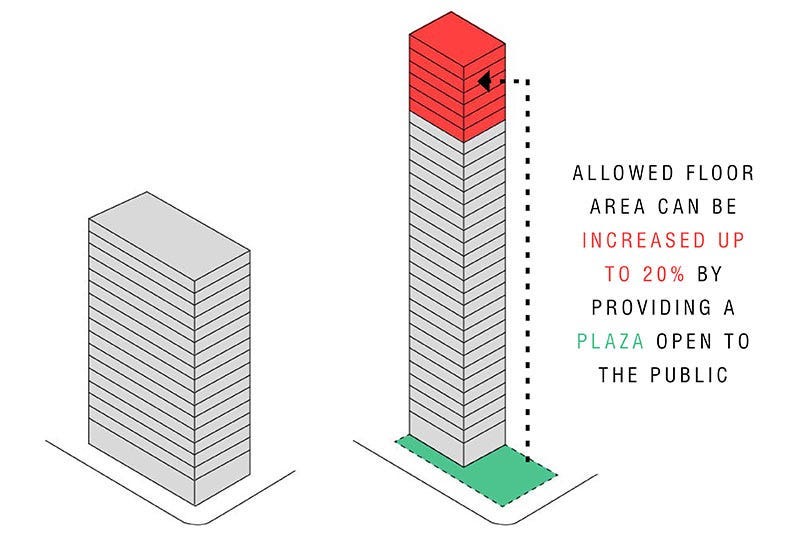

What’s different is who maintains the spaces, which as the name suggests, are private property owners. They create the POPS in exchange for additional floor area or special waivers for buildings they are developing, with the additional “floor area ratio” (FAR) allowing for more stories or larger floor plates that would otherwise be unpermitted through existing zoning laws.

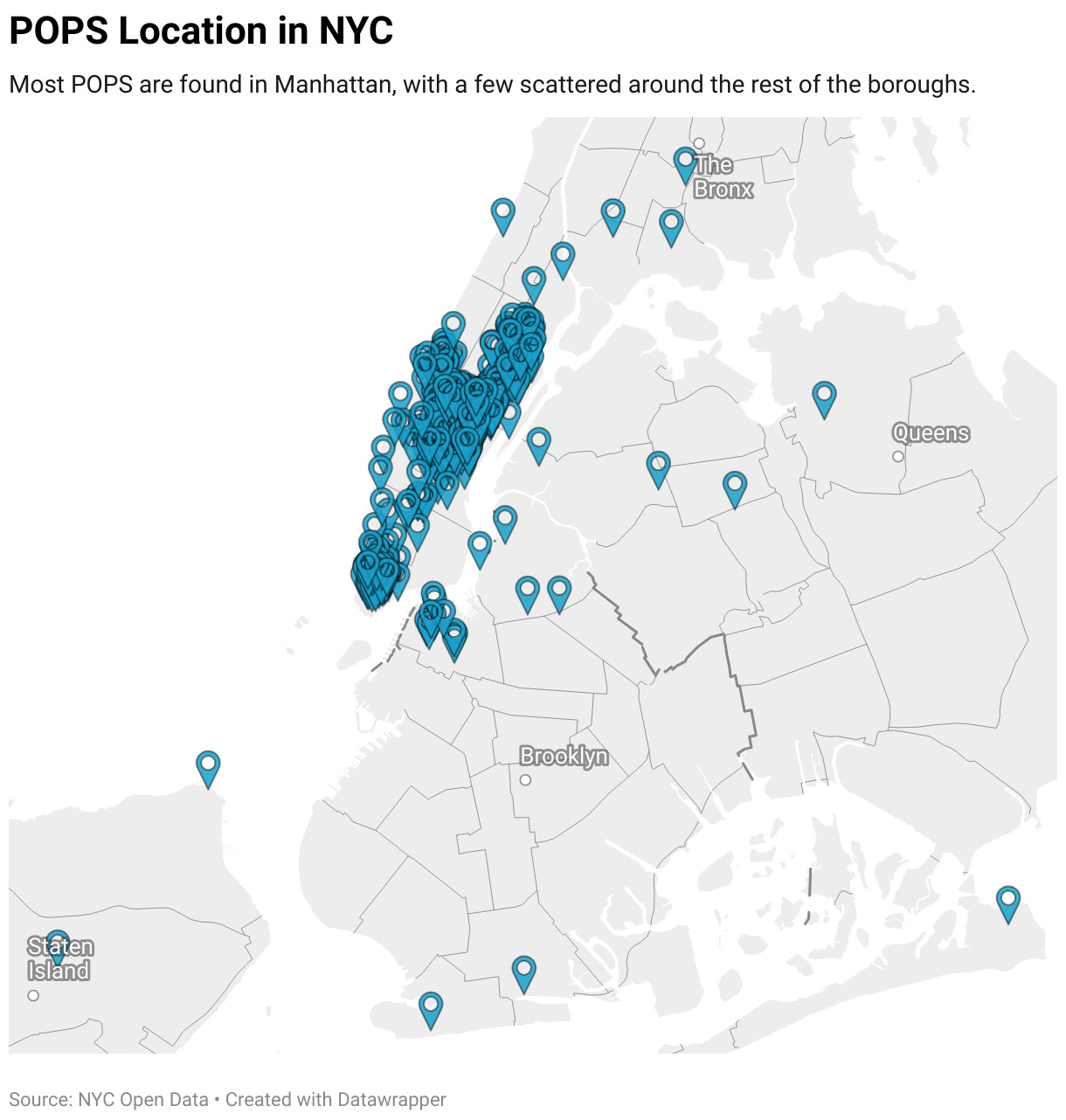

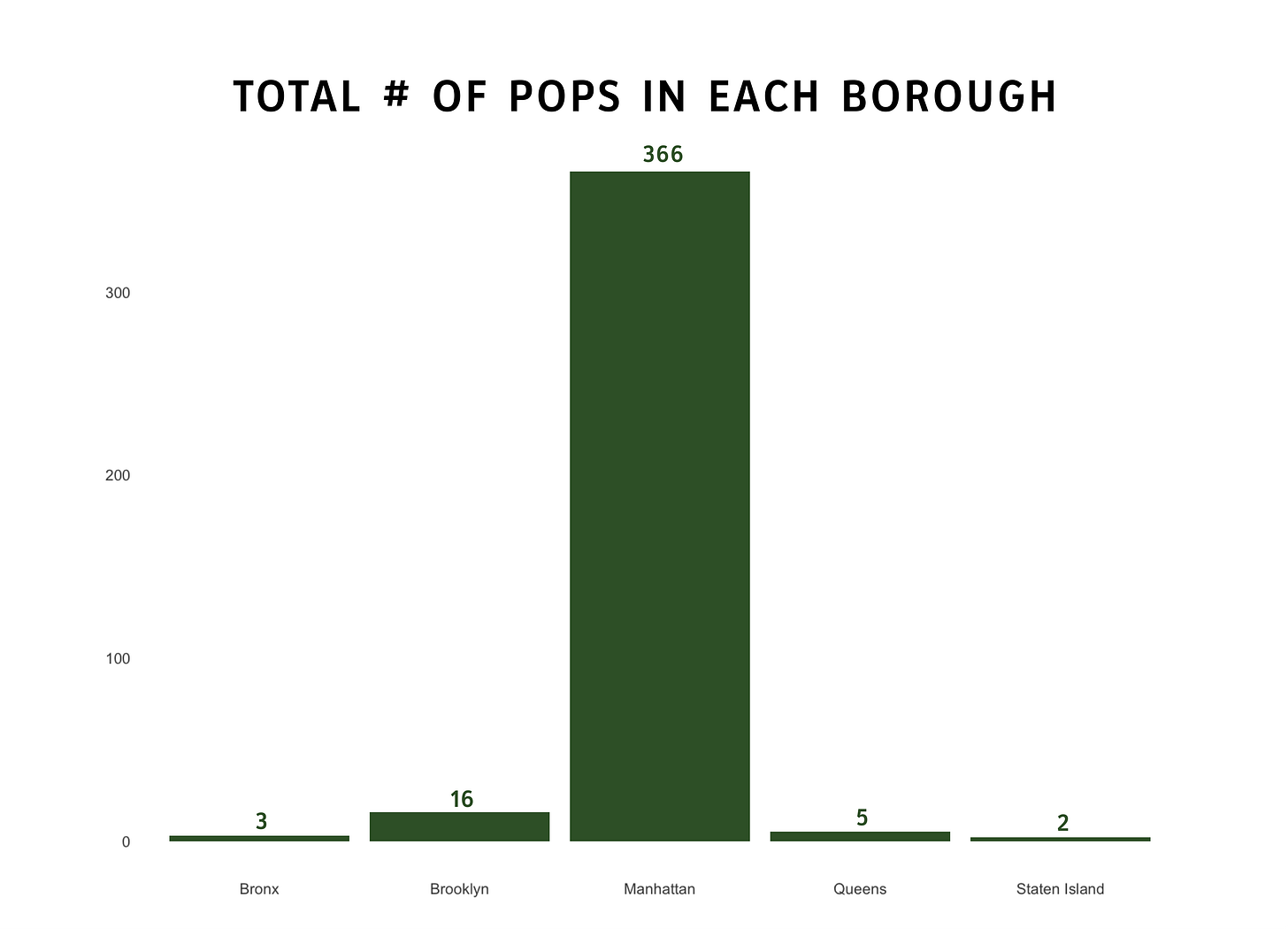

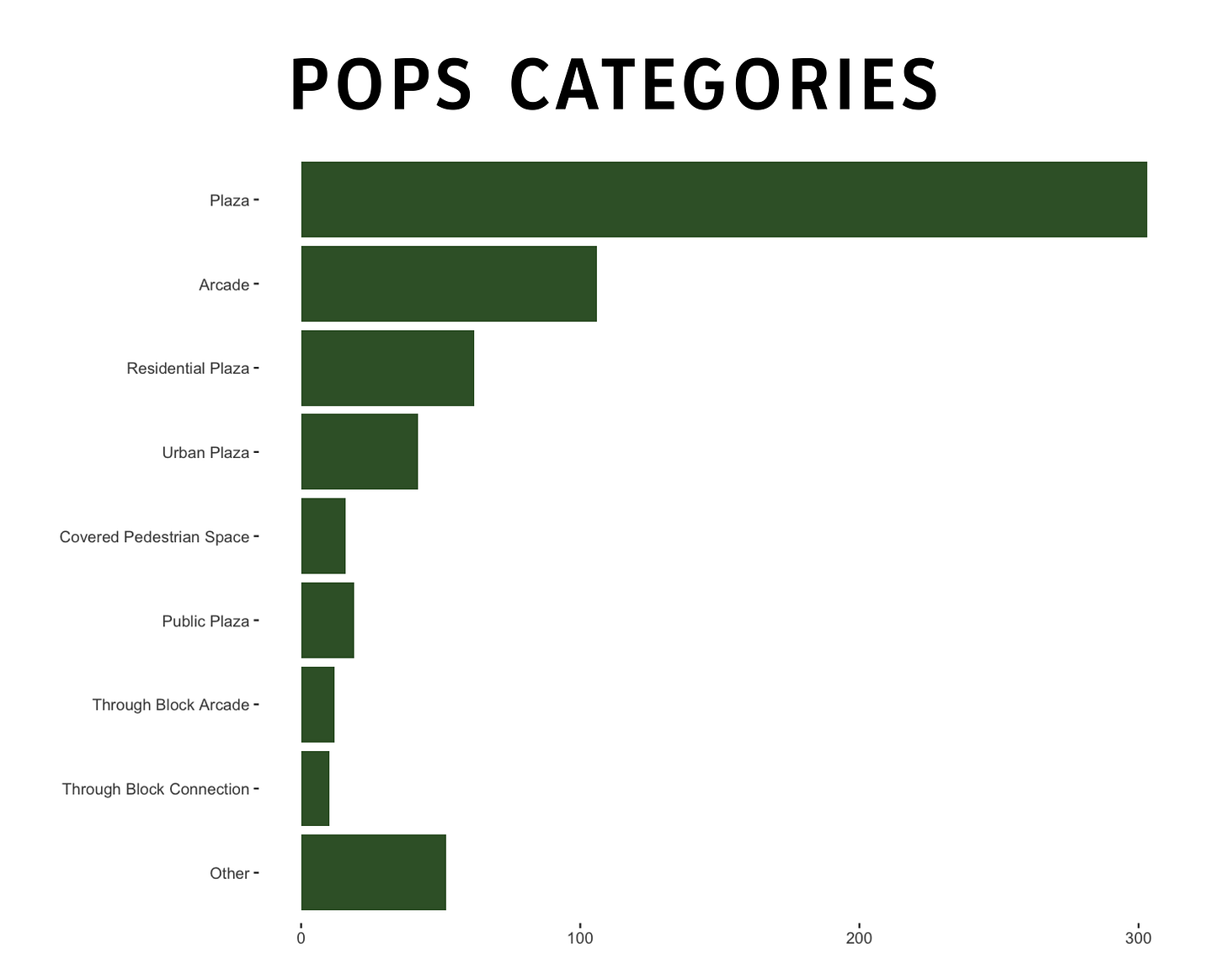

Based on the POPS NYC Open Database, over 390 buildings have created over 600 POPS since 1961, most often located in Manhattan’s midtown and downtown districts as they are closer to developer commercial buildings. There’s a variety of different POPS, with the most popular being plazas and arcades.

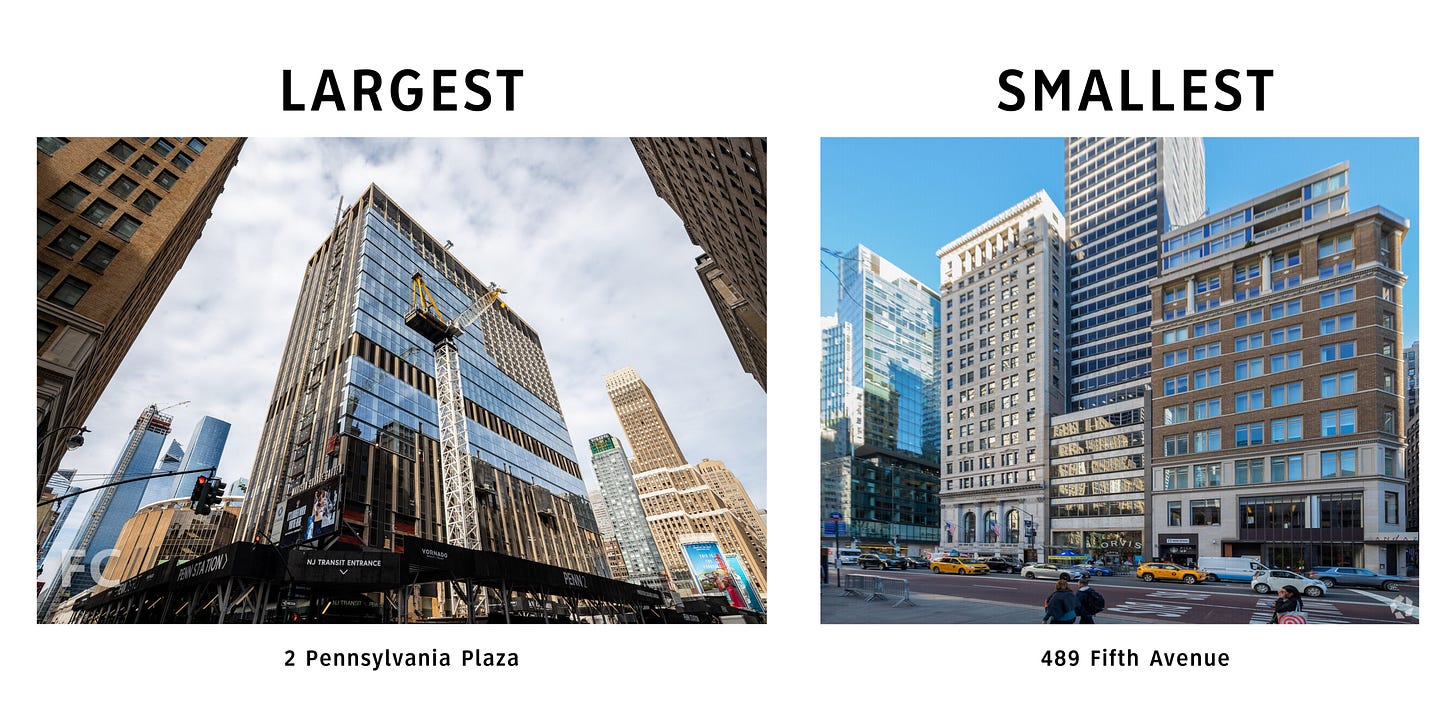

The spaces range dramatically in size, with the biggest POPS being a mix of two plazas totaling at 6,218,764 square feet at 2 Pennsylvania Plaza, containing office buildings and Madison Square Garden. The smallest POPS that’s an actual space is an arcade at 510 square feet at 489 Fifth Avenue, with many sidewalk and corridor spaces technically being smaller.

Other cities followed NYC’s lead, also creating POPS, with over 200 in San Francisco, over 200 in Toronto, over 50 in London, over 40 in Seattle, over 40 in Seoul, and a number in Dublin.

Compared to other comparable public spaces, like parks/playgrounds, plazas, beaches, community gardens, public housing open space, POPS make up a small portion of the amount of public space that is available for the general public to use. Parks alone make up over 29,000 acres, or over 1 billion square feet (more like 2.6 billion square feet if you sum up the total acreage from open parks data) — POPS make up 10 million square feet.

However, while POPS may only represent a fairly small portion of overall public space, their unique context within the urban landscape requires a closer examination. Because of their strategic location in high-density areas and important value in development right negotiations, POPS warrant careful scrutiny to ensure they actually serve the public good.

How POPS came to be

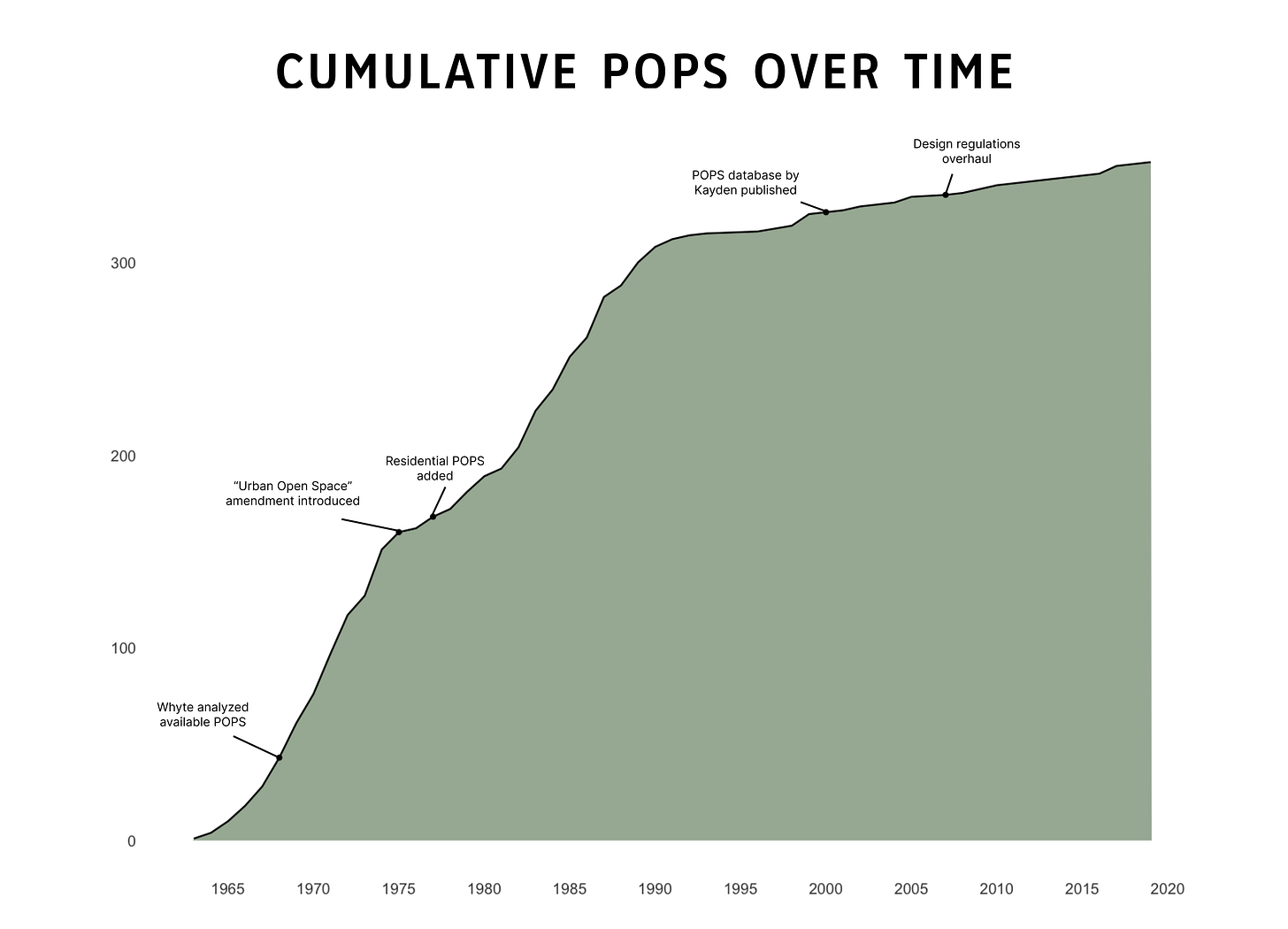

The creation of POPS came from the adoption of new zoning resolutions in 1961, when New York City decided to update the initial landmark regulations created in 1916 to include public spaces as a zoning tool.

Coming out of World War II, NYC experienced an explosive amount of economic and population growth, leading to an immediate need to build more housing and commercial buildings.

Many developers felt that the original 1916 ordinances establishing guidelines for “setbacks,” or mandatory distances a building must maintain from streets or other buildings, were too restrictive. At the same time, the general public increased advocacy and demand for better open spaces, as it became more difficult to receive sunlight in denser areas with skyscrapers continuing to be erected taller and taller, and more challenging to find meeting spaces as automobiles became more prevalent, taking up street space.

General modernist architecture and urban planning design philosophy started to shift as well, with active influence from folks like Le Corbusier and the Garden City movement pushing for more mixed-use developments, public plazas and pedestrian-friendly space.

During this time, the city held relatively low taxes to encourage growth, and thus drastically cut public budgets, leading to less financial support for public spaces. And so, with the support of folks like William H., Whyte, an incredibly vocal urbanist and journalist who researched public spaces, the city decided to address a number of these issues by trading one perceived public good (limitations on building height and mass) for another (more public spaces).

Codified in New York City’s 1961 Zoning Resolution, developers were able to add additional floors, increase floor space, or receive special waivers to their projects if they also built and maintained accessible public spaces, specifically plazas or arcades known as atria.

However, there were limited dimensional and design requirements, permitting only flagpoles, driveways, and garage entrances. Developers also only had to follow basic compliance with floor area computations with the Department of Buildings (DOB) and did not require the Department of City Planning (DCP) to review the space.

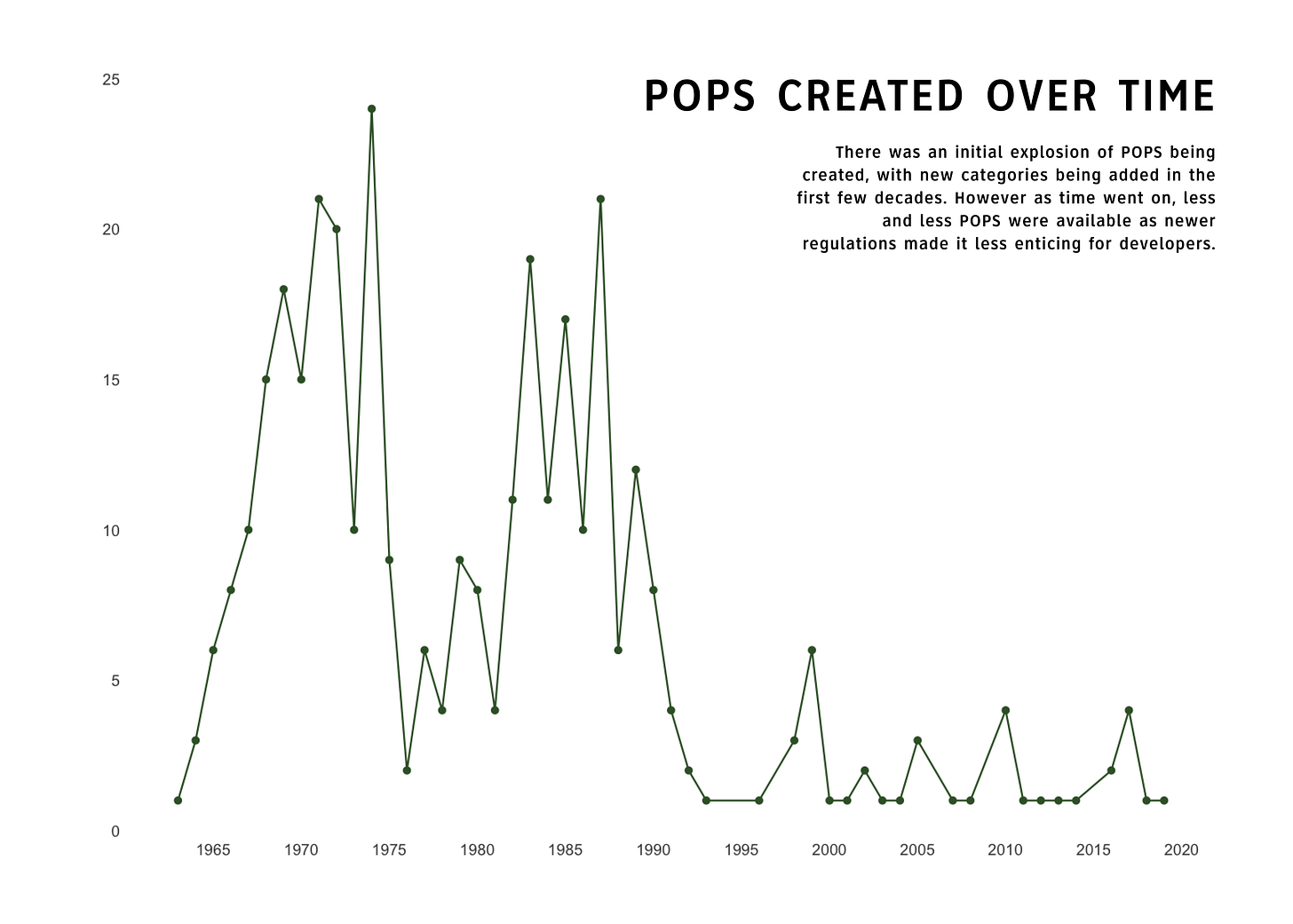

POPS blew up in popularity for developers, as it was fairly low cost, added additional value to a building, and led to additional space for their clients, leading to over XX being built.

This bonus led to new types of spaces to be included as a POPS type, including, but not limited to, elevated sunken plazas, through block arcades, covered pedestrian spaces, and open-air concourses.

Whyte later analyzed these spaces and their effectiveness, discovering that while the built POPS did bring light and air to the public space, the space was not actually usable. He advocated for the design and management improvements that would make them more functional and welcoming to the public, instead of just wide-swept underused expanses of pavement that provided limited value.

This work translated into the “Urban Open Space” amendment in 1975, establishing three types of POPS: open air concourse, sidewalk widening, and urban plaza. Specific amenities were required, including seating, plants, lighting, ADA access and signage. It also ensured that there must be a certification by the DCP chairperson and the DOB chairperson to meet the new design standards.

Yet these design principles were met with a similar problem as they were not detailed enough, nor were they actually enforced and so many of the POPS remained difficult to access or even be understood as a public space. So while there continued to be new types of POPS added, including residential plazas for high-density residential districts, many other POPS categories were limited and restricted.

By 2000, Harvard professor Jerold S. Kayden worked with the DCP and Municipal Art Society (MAS) to publish a new database with detailed information about POPS, serving as a basis to understand where and how these spaces were used. This database is the same database updated and maintained today by New York Open Data, serving as the source for all of the data I am sharing in this report.

This work eventually led to 2007 provisions that overhauled the design regulations once more, leading to better clarification.

The design principles set out in the updated zoning resolution state that the space must be:

Open and Inviting: The space must be easily understood as open for the public. This can be done with design elements such as signage, trees, and seating.

Safe, Secure, and Accessible:It must be located at or ADA accessible from the sidewalk, with adequate seating and lighting. It also must have a performance bond posted to ensure proper maintenance.

Comfortable and Engaging: The space must also have amenities that encourage folks to use the space such as open air cafes or kiosks, with driveways and exhaust vents being prohibited.

At the same time, this update also finally introduced a process to support owners to redesign or modify their existing plaza to ensure that these POPS are up to standard. But it wasn’t until 2017 that penalties and fines were also approved by city council to charge developers for not updating POPS to meet the new standards.

Public in name only

It’s easy to see how POPS can provide a huge value for developers and the general public if managed properly. But even with all of the regulations and updates, the lack of enforcement and publicity by the City to update these public spaces make it difficult to ascertain if a majority of these POPS are truly providing value as public spaces.

The city comptroller wrote a scathing report back in 2017 about the failure between the DOB and DCP to uphold POPS to the standards set. Inspecting all of the POPS available at the time, they found that over half of the spaces failed to provide the required public amenities for a number of reasons including, but not limited to:

A lack of signage indicating the space was a POPS.

Restaurants were using public space for seating.

Public access through sidewalks or doors were limited or denied.

The amenities were not functioning or available.

The amenities simply did not exist.

Many of these cases have also existed for years without direct action from the city, with over 80% having not been inspected in at least 4 years. Even with those that have been inspected, a majority of them had issues and did not receive violations.

Since then, not much progress has been made, with only 53 violations made since 2018, as of May 2024, according to my manual count through the DOB Monthly Enforcement Bulletins. And it’s not clear to me if DCP has made an effort to publicize this issue to folks, as querying through the 311 reports made to DOB for POPS showed 0 results.

At any rate, perusing through Google Street View and walking through various POPS throughout the city displays the failure of POPS to meet the design standards they should be meeting. And the public is all the worse for it.

Where to go from here

We know that POPS can be important and valuable for improving business districts, especially with the 2022 New New York initiative and the followup report from Chief Public Realm officer Ya-Ting Liu about the Realm of Possibility for the future.

The city is coming up soon on the three-year compliance cycle and need to move forward into taking action on these issues.

But there are still a number of questions that need to be answered.

Is there somewhere I can go to see POPS today?

The city maintains a map of POPS, but there is no active catalog of POPS that are still in violation of the guidelines, similar to the work the city did back in 2000 and 2007. Tracking POPS that have received violations and current updates to its progress remain difficult to follow.

Is the collaboration between the DOB and DCP the best approach for managing POPS?

The lack of communication and insufficient number of folks available to prioritize POPS is evident, and may need to require alternative incentives and solutions to ensure they get support.

Is the city making a worthwhile tradeoff by providing these public spaces to developers in return for higher FAR, or is the public getting the short-end of the stick?

This remains a potential research topic, as there seem to be no clear guidelines around the economic and financial impact of POPS. Debates focused on if the city should continue to allow for POPS to support development, or if it is better for the public to have the city manage and create actual public spaces remain.

Do other cities have this problem? If they do, how do they handle this issue and ensure that POPS design guidelines are enforced?

It’d be interesting to see if there are lessons other cities could teach NYC about successful POPS implementation. The current fines do not appear adequate enough to persuade developers into modernizing the existing POPS. The current fines are a measly $4K for the first offense, $10K for an additional offense, and a penalty of $250 for each month they fail to comply.

What is the role POPS play in preserving neighborhood culture and can they add value to a community the same way public spaces can?

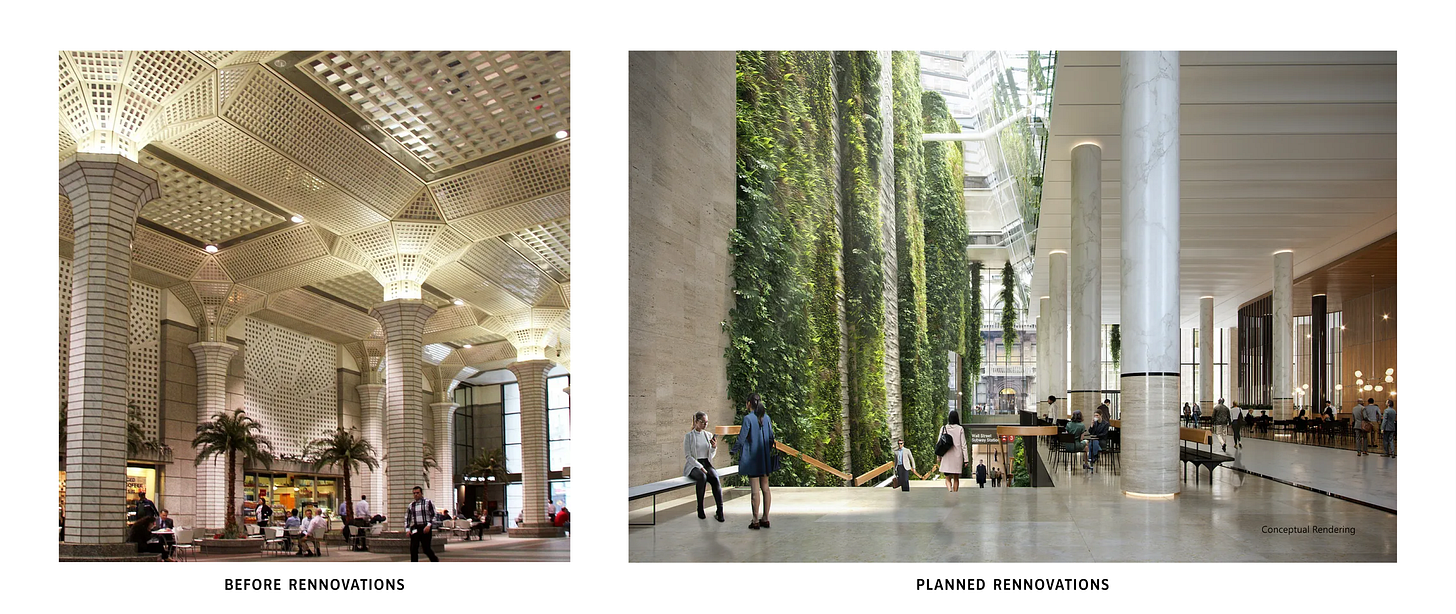

60 Wall Street is a prime example of how a POPS can be important to the community. Built back in 1989 by JP Morgan Chase as a 55-story postmodern skyscraper by Kevin Roche, the indoor atrium was designed as a quiet oasis, surrounded by the chaotic financial district, decorated with a grand, European aesthetic featuring tall columns, marble floors, and potted plants.

Like many POPS in the city, it is open to the public 24/7, which made it a prime location for many to meet, including for protesters during the Occupy Wall Street movement. Deutsche Bank acquired the entire building in 2001, and the responsibility to maintain it, before selling it to Paramount Group in 2007.

As of August 2024, 60 Wall Street has been closed down for renovations, with plans to modernize the design and hopefully bring back more leases to the financial district. There was some immediate public backlash to the space’s distinctive character and historical significance, yet it seems to not have made much of a difference as plans move forward to change the space into a taller atrium with fewer columns, more skylight, and a green wall from floor to ceiling.

The last time I visited, the place definitely showed its age due to both an older design and a lack of maintenance. We’ll have to wait and see if this space can live up to expectations and reestablish itself as a true public space for the community. Yet, it’s hard not to remain skeptical with the lack of robust enforcement and history of neglect, which may lead it to follow the same path as many other POPS that feel more like private spaces in public disguise.

The story of 60 Wall Street isn’t just about one space — it’s a reflection of the ongoing struggle to preserve and provide truly accessible public places, while balancing the needs of private developers and the public. Time will tell if POPS can evolve into true public assets, moving past their commercial roots, and foster the sense of belonging and community the city so desperately needs.