The Case for Congestion Pricing

Why it's the best tool to improve public transportation and reduce traffic congestion

As I talk about congestion pricing with friends, I decided it was high time to put it down on paper instead of having numbers and facts live around disparate messages. Feel free to use this page as a starting point for why congestion pricing is important to you.

Updated: August 26, 2024 due to congestion pricing stop and related news.

It’s been almost two months since Governor Kathy Hochul indefinitely paused NYC’s congestion pricing plan. Her decision to stop the plan came at a major surprise when she announced it back on June 5, 2024.

This delay is a major setback for everyone living in the city as it drastically stops plans for a $15B annual revenue stream to help improve public transportation, while also stubbornly maintaining the status quo around traffic congestion, noise pollution and vehicle emissions in the city. There was estimated to be around 100,000 fewer vehicles entering the zone every day, relieving crowding in one of the most congested districts in the country.

And while there are some very valid concerns about its implementation, fear about what is expected, and who will be bearing this increase in cost, I’m making the case that Gov. Hochul should implement congestion pricing as meant to.

What is congestion pricing?

In NYC, this congestion pricing plan is different depending on the type of vehicle you are and when you are driving. Peak period rates are from 5am-9pm (weekday) and 9am-9pm (weekends), with all other times being overnight period rates.

What would I be paying?

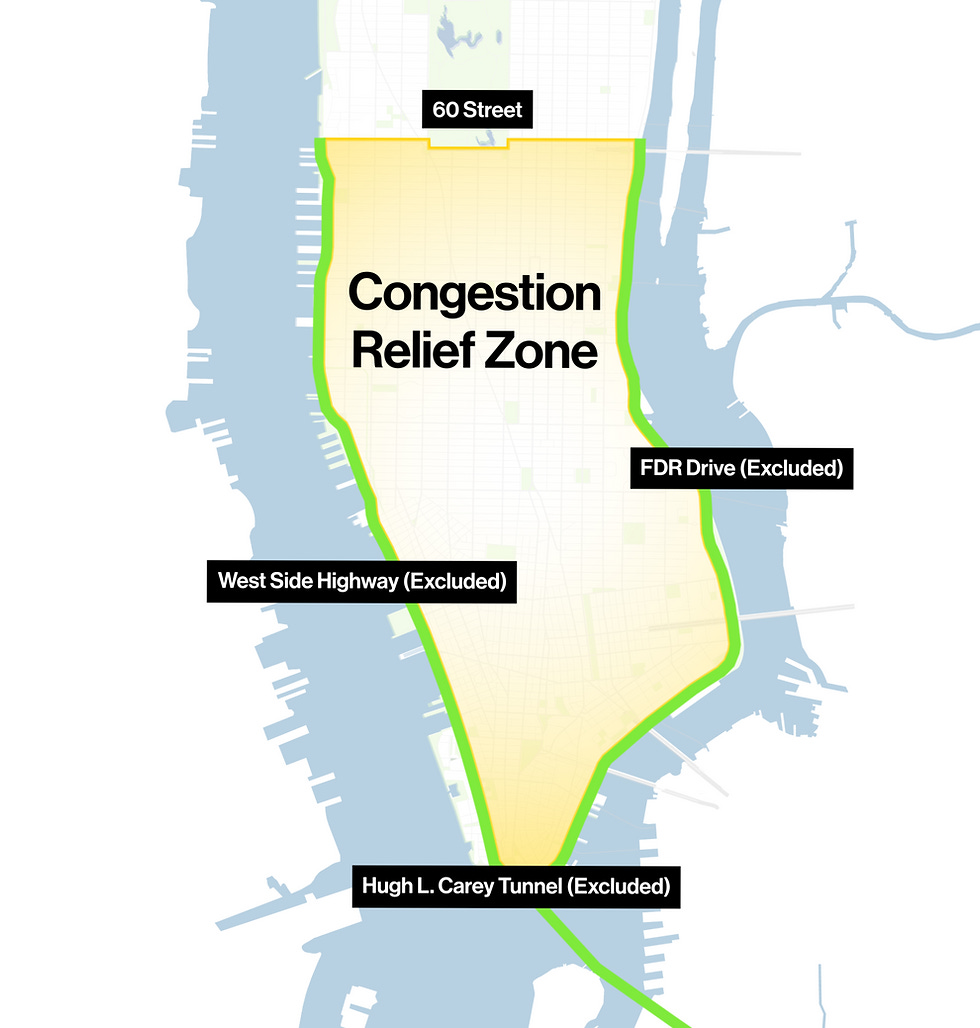

For the majority of drivers, passenger and commercial (sedan, SUVs, pick-up trucks, and small vans) drivers will pay $15 upon entering Manhattan south of 60th street, dropping to $3.75 during overnight. Motorcycles pay $7.50 during the day and $1.75 at night. This charge would only happen once for drivers entering the zone that day, meaning if you were to exit and return back, you would only be charged for the first time.

Trucks and buses are charged either $24 or $36 during the day ($6 or $9 at night, respectively) depending on their size and function. Certain trucks and buses are exempt. These vehicles must pay each time they enter the zone.

Yellow taxis, green cabs or black car passengers will have to pay $1.25 toll for each trip, whereas Uber, Lyft, and other ride-shares have to pay $2.50.

Any exemptions?

A number of vehicles will be exempt, including emergency vehicles, those carrying people with disabilities, and school buses. Certain specialized government trucks and commuter buses and vans will also be exempt. Low-income drivers will get a 50% discount, and a tax credit for low-income residents who live south of 60th street will also be provided.

Trips alongside the FDR Drive and West Side Highway will not be charged.

What if I paid for entering any of the tunnels?

Upon exiting any of the tunnels and entering the congestion zone will refund money for paying that toll charge including $5 for cars, $2.50 for motorcycles, $12 for small trucks and buses, $20 for large trucks and tour buses. These tunnels include the Lincoln Tunnel, the Holland Tunnel, the Queens-Midtown Tunnel, or the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel.

How are we going to enforce congestion pricing?

The MTA installed infrared cameras that tag E-ZPasses and photograph license plates around 110 locations in Manhattan, mostly on existing street poles, walkways or overpasses. The MTA contracted private company TransCore in 2019 to build this infrastructure. They also added readers at select points in FDR and the West Side Highway, recording the times the vehicles pass through and only charging a toll if vehicles stop being detected by toll equipment along the two highways.

A valid concern with photographing license plates are the many cars that find new ways to cover up their plates, which has also recently ticked up in frequency. The NYPD is still working on finding better ways to deal with this issue.

Now that congestion pricing is on pause, there’s also a real concern behind what these cameras may be used for today. The MTA has announced no plans, but it could be used to collect more data on drivers, but also just be additional tools for surveillance, without the benefits of congestion pricing.

Why is congestion pricing a good idea?

Traffic congestion has always been a major problem. Road wear and tear is funded through general and fuel taxes, with tolls supplementing any additional costs to construct, maintain or improve those infrastructure projects.

But as a multitude of major external problems around urban development and climate change continue to rise around traffic congestion, economists like Arthur Pigou and William Vickrey saw taxation as a way to align private costs with more social costs to reduce the negative externalities of road usage — aka, congestion pricing.

This is how I like about why congestion pricing conceptually makes sense:

Each additional vehicle on the road adds to increased travel time, increased fuel consumption, increased environmental pollution, and increased chance of an accident on the road — external costs that affect everyone, including the driver.

Road space is limited, especially during peak times. Dynamic pricing during peak time ensures that the road is for those that value it the most and can afford to pay for it through the idea of marginal social cost, essentially correcting a market failure (given road usage today is “free”) as the price reflects the cost of one additional driver using the road during peak times.

Prices will shift behavioral change with less drivers, mitigating the risks of congestion and thus further reducing the external costs, as drivers consider other travel options, alternative routes or adjust schedules, leading to a safer road and less noise/emission pollution. Goods and services will be delivered faster.

With additional revenue for improvements, this can be invested into transportation infrastructure that is needed to help the majority of folks in that region, which for most cities is public transit. This incentivizes even more folks to find alternatives to drive, further reducing externality costs with congestion.

By compensating social congestion costs of individual drivers through private congestion pricing, it encourages more efficient road use and reduces congestion for an overall more sustainable and equitable transportation system.

Feel free to read more about Vickrey’s work. Additional things he advocates revolve around parking charges, which itself is a hot button topic that I will write more about in a future piece.

What changed over time?

Many cities began implementing their own versions of congestion pricing to see if they could reduce traffic and found major success, proving the theories proposed by economists around congestion pricing.

Singapore was one of the first major cities to introduce a version of congestion pricing, all the way back in 1975, with real-time data to adjust to traffic flow. Combined with increased parking fees, license plate enforcement, around 20% of congestion decreased and a revenue 9x the cost. They continued with a second phase in 1998 with a more automatic pricing system, increased buses and bus frequency, and new HOV+4 lanes — offsetting the $25M cost with around $150M in net revenue. Traffic was drastically reduced, with increased average speeds for those still driving, in addition to increased ridership and public infrastructure improvements.

London started investigating congestion pricing with feasibility surveys in 1964, before finally introducing a plan in central neighborhoods including the Inner Ring Road in 2003, reducing congestion by 30%, improving travel time reliability, and lowering vehicle emissions. Stockholm initially ran a trial during 2006, before making it permanent as it saw around 30-50% of its overall traffic reduce and overall pollution level dramatically decrease, with a slight 4% increase to public transit usage.

Other cities including Oslo, Milan, Beijing, and Dubai have all introduced or are in the process of introducing a form of congestion pricing that has brought about success at reducing traffic and improving public transportation.

Yet, there is one consistent thread through most of these implementations: negative public opinion before rollout transitions into fairly positive pivot after rollout.

Researchers in Oslo tried to collect information around this, but there are limited studies tracking the behavior folks had before and after congestion pricing was implemented in cities. Factors such as their willingness to pay, whether residents drive a car, their age and educational level, fuel type and geographic area all play into determining whether they are willing to try out congestion pricing.

What is obvious is that targeting groups that are more likely to have negative attitudes towards congestion pricing is critical to ensuring there is increase support. And this can be done by addressing some of the concerns folks may have.

What are some of its biggest criticisms?

One of the biggest challenges is the mental paradigm shift required to move from assuming that the road is free for drivers to having to pay for this amenity. In fact, most folks at public hearings are pushing back that they don’t believe they should be penalized for being able to afford a car and live in Manhattan.

But it is specifically these types of folks that are most capable of paying the fees if they are committed to driving around the city. Drivers must begin seeing this as part of the investment to owning and operating a car within the area, even if it may be hard to stomach the increased cost.

But don’t a lot of people drive into the city for work? What about middle class or lower-income workers that can’t handle the additional cost?

The Community Service Society of New York (CSS) has consistently debunked this question, using available census data from the 2015-2019 American Community Survey Five-Year.

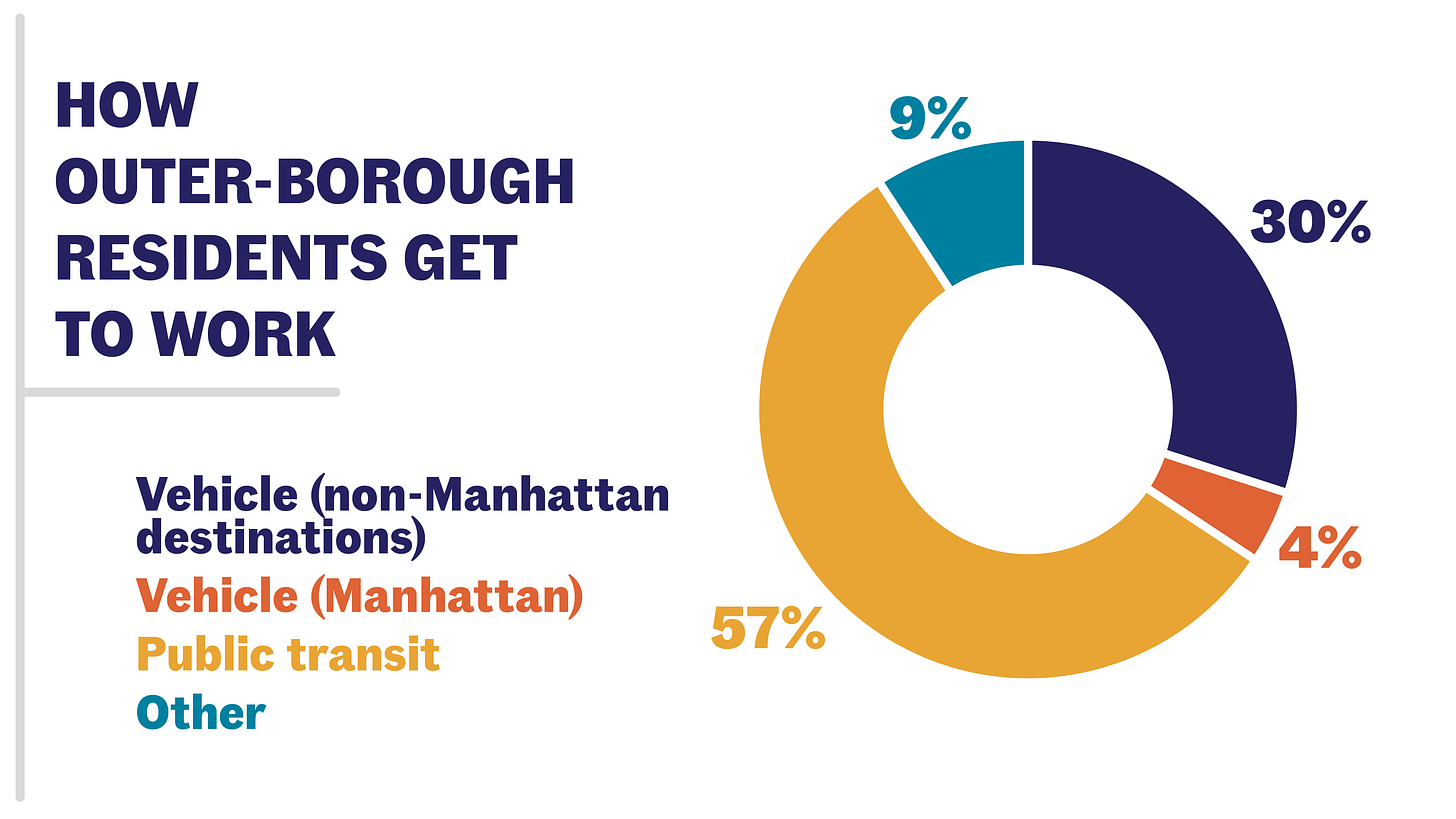

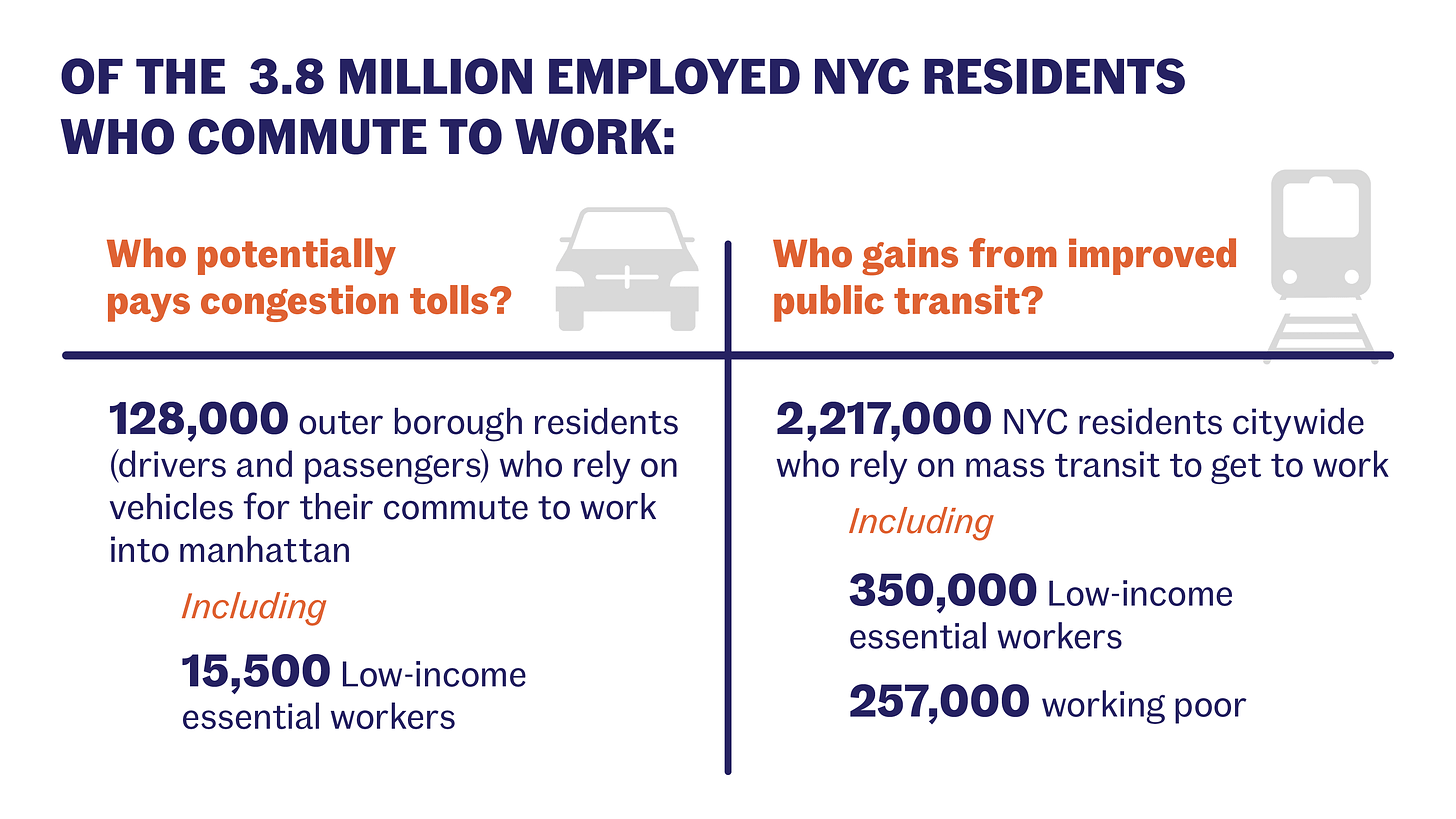

No more than 4% of all income from outer-borough residents (Brooklyn, Bronx, Queens and Staten Island) will regularly pay a congestion fee, as a majority of residents depend on public transit for work. Only 2% of those in poverty (around 5000 residents) would be charged with congestion pricing, with many of those able to apply for discounts.

Most New Yorkers that have cars in the outer boroughs are well off and should be the ones targeted by congestion pricing. Most low-income essential workers use public transportation to enter the city, with only 3% potentially being charged as part of their daily commute.

This not only indicates the lack of concern for people driving into the city for work, but it also stands that everyone, especially those with lower incomes, benefits from increased revenue to improve public transportation. And those that need to drive will reach their destination faster, increasing speed for goods and services.

I agree that there is a financial challenge for workers that require a car to carry tools, such as construction workers, electricians and other tradespeople. Gig drivers or workers that work at non-typical hours will also need to pay an additional cost.

And it is not always certain where this increase in cost will go. Goods and service drivers most likely pass this additional cost to their clients in the center of the city, making their service more expensive and adjust demand as union groups from across NJ and around NYC have voiced their dissent consistently with multiple lawsuits designed to block the plan, including one by NJ Gov. Phil Murphy.

But reviewing the data from other cities that have implemented congestion pricing, this financial burden doesn’t appear to have as large of an effect on these groups as many argue.

This does not mean that there should not be constant communication with workers. There just currently is not a good way to understand the types of drivers entering the city without seeing the effect after congestion pricing is implemented — adjustments should be made if needed to support different groups if there are drastic unintended effects.

This isn’t the best answer, but considering the number of people we can and will support with all the benefits of congestion pricing, it may be a necessary initial tradeoff.

Has there been enough increased service to support those commuting from outer boroughs instead of driving?

This is one of the other major problems with current plan. Union groups like the Transport Workers Union believe their has not been enough increased bus service before the pricing plan.

The first rollout of the congestion pricing plan is at its most critical as increased bus services and more reliable trains requires a dedicated commitment to improve the transportation conditions of those commuting from further locations.

We must continue to be vigilant to ensure the MTA or the city expands transit for folks that commute into the city. Consistent lessons from other cities is that there must be actionable public transit improvements, additional safety for bikers/commuters, and increased enforcement of parking and traffic to see success.

Won’t we be directing traffic towards other neighborhoods instead then? Will this just be moving congestion towards other parts of NYC, maybe even a few blocks up?

There’s the potential for this to happen, and will require active readjustment and monitoring to see how people respond. Drivers may immediately respond to avoiding fees by driving to nearby streets or neighborhoods that won’t expect this increased amount of traffic. Precautions around traffic calming measures to discourage cut-through traffic like speed bumps, road closures, and community support can help take care of immediate traffic problems.

Outer-borough residents may not see this initial benefit, as this mainly focuses on Manhattan — but people will adjust. Over time, people will normalize to deciding whether they are willing to take more time or money to look for ways around congestion pricing, pay for congestion pricing, or begin taking transit. This is the main purpose of the policy.

Why is congestion pricing one of the biggest ways to help generate revenue for public transit? Why not address other ways to get revenue like reducing fare evasion or receiving more government grants?

The impact of fare evasion and other sources of revenue are significantly smaller at scale compared to congestion pricing.

Fare evasion is estimated to amount to $690M lost, compared to the $15B from congestion pricing. The approach to tackling fare evasion also requires investigation per transit system and location, making it less predictable to solve and maintain. This is not to say that we shouldn’t solve fare evasion, but the MTA is currently already working on addressing this, which in turn also requires more funding that could be benefitted from congestion pricing.

General discussion to direct more government grants toward public transit is difficult to achieve, but will require a major cultural shift. This will take time and will not have as much of an immediate impact in the national dialogue compared to congestion pricing.

Why are we even focusing on congestion pricing over other problems the city is facing around traffic and public transportation?

I agree! There are so many other problems the city is facing around traffic in the streets including bus and bike lanes being blocked by delivery trucks, construction workers, police cars; inefficient street design leading to confusing traffic jams with pedestrians and bikers; and just generally double-parked vehicles in random streets.

If anything, congestion pricing will help to reduce the overall number of cars on the road to allow for more space for those driving and cause less of these things to happen. But yes, these are all problems the city is still trying to address!

How long is it going to take to see any of the benefits from congestion pricing? It’s going to take longer than waiting in traffic.

It will take some time for benefits to be seen directly in public transit. Keep reading for a list of those improvements. But immediate benefits you may see include reduced traffic, reduced noise, and reduced pollution.

What would the revenue earned by congestion pricing go towards?

The goal of the revenue is to spend around 80% of it on capital improvements to the subway and bus system, with the rest to be spent on the LIRR and Metro-North.

Money generated from the tolls is focused on a few main areas:

Accessibility additions and replacements in stations with ramps, escalator and elevators that require updates.

New and more reliable railcars and buses, making them more electric, more reliable and feel more modern with updated passenger information screens and brighter lighting.

Signal modification to increase service reliability, reduce delays and accurately predict time to arrival for subway cars driving on the tracks.

General station improvements to improve the overall customer experience and repairing critical infrastructure, with other structural components and upgrades of work equipment.

General structure infrastructure improvements including power delivery, track upgrades, bridge repairs, and customer communication radio systems.

Building out the Second Avenue Subway extending the Q up to 106, 116 and 125th street to connect with Metro North and M60 Bus Service to LaGuardia (although personally I can’t wait till they add a subway directly to LGA)

In addition, leading up to the congestion pricing plan, the MTA will work on increasing service on 12 subway lines, rolling out a redesign with the bus network, and making a large service increase with the Long Island Rail Road.

How long has this plan been discussed in NYC?

Congestion pricing has been talked about for over 50 years already, and this plan would have been the first of its kind in the U.S.

Ever since it was originally floated around by urban planners and economists back in the 1970s-1990s, it has slowly gained traction through the years despite concerns around its impact towards businesses and residents. Mayor Michael Bloomberg back in 2007 announced congestion pricing below 86th street, before it got blocked by the New York State Assembly. Other advocacy groups, city officials, and even previous Gov. Andrew Cuomo tried to revive discussions and implement congestion pricing during the 2010s.

With the continued deterioration of the subway and lack of support to get funding, it became almost critical for a source of revenue to address NYC’s public transit. The rise of ride-sharing contributed to the very real and perceived increase of traffic congestion, leading folks to once again push towards congestion pricing.

Finally in 2019, that the New York State Legislature passed congestion pricing as part of the state budget, due to the hard work of groups like Transportation Alternative, Regional Plan Association, Tri-State Transportation Campaign, Riders Alliance, NYC Environmental Justice Alliance, and the Natural Resources Defense Council.

The implementation of cameras, toll gantries, and other environmental assessments was delayed due to COVID-19 and slow federal approval from the U.S. Department of Transportation (with a failure from the Trump Administration to provide guidance for the mandatory environmental review), before finally reaching the appropriate guidance from the Biden Administration. The 16-month review process then pushed the date to June 30th, 2024 before Gov. Hochul stopped it.

The difficulty of getting congestion pricing passed for NYC cannot be understated as it required approval from multiple different municipalities at multiple different levels. Compared to cities like London, this decision had to go through the city’s DOT, the state-run MTA, New Jersey’s PATH and NJ Transit, and Amtrak.

What’s happening now?

That’s the big question isn’t it?

Gov. Hochul halted rolling out congestion pricing because of proposed economic/equity concerns, general political pressure, and potential public backlash. She said it was too risky for the economy, with cited conversations that $15 is too high. But hope I’ve proven above that there is a strong case to try out congestion pricing.

We’re still waiting to see what Gov. Hochul is going to do to make this up. If anything, most people believe this move is going to backfire for her. Lawsuits are now being rolled out to contest her halt combatting her ability to stop this type of rollout and her oversight on the project.

I’ll follow up this piece with what can potentially be done to get this over the line.

Even after all this, I’m still not convinced.

While I’d like to say that may just be somewhere we agree to disagree, I will keep trying to work at convincing folks like you that change must happen to traffic. This is not the city I believe most of us want to live in and it can be better. It’s hard to conceptualize this change.

It may just take going to a place that has congestion pricing to change your mind.